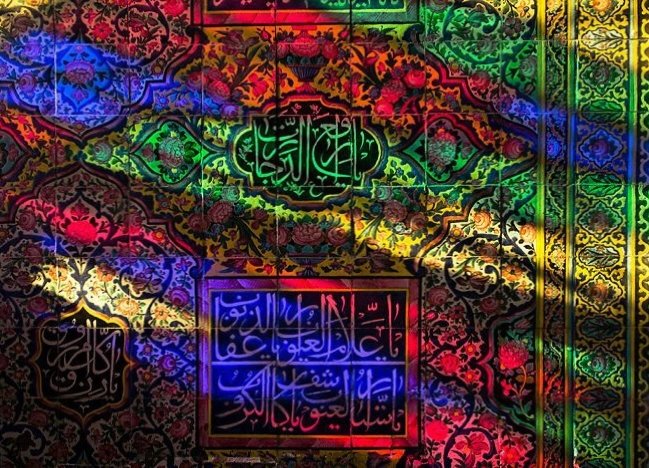

Cosmogram. Image source unknown. Found image.

If the imaginal is a world, then architecture has always been one of its privileged thresholds.

Long before architecture became a profession, a discipline, or an object of visual consumption, it functioned as a mediating practice—a way of giving form to meanings that were already operative within a shared order of reality. Building was not the production of novelty, nor the assertion of authorship over space. It was an act of translation: bringing imaginal intelligibility into spatial presence without exhausting it.

In this sense, architecture did not represent the imaginal. It hosted it.

Traditional built environments understood space as layered. A wall was never just a boundary, nor a courtyard merely an empty void. Thresholds mattered because reality itself was understood as graded. Doors, passages, gardens, domes, and mihrabs were not symbolic decorations applied to neutral matter; they were spatial articulations of ontological difference—ways of orienting the body and the soul within a world that exceeded immediate visibility.

Nasir-ol-Molk Mosque (مسجد نصیرالملک). Shiraz, Iran. Photo by Ramin Rahmani Nejad, 2012.

Architecture thus belonged to the same economy as the imaginal: an economy of between-ness. It stood between the sensible and the invisible, between memory and expectation, between life and death. It gave shape to what could not be grasped directly, without reducing it to abstraction.

This is why certain spaces were never meant to be “used” in the modern sense. Cemeteries were not sites of disposal but places of encounter. Shrines were not monuments to the past but nodes of presence. Gardens were not aesthetic retreats but cosmological diagrams—ordered spaces where water, light, geometry, and growth disclosed a reality more generous than utility.

What these spaces shared was not style, but orientation. They were not designed to persuade, impress, or entertain. They were designed to attune. Their success was measured not by spectacle, but by the quality of attention they cultivated.

The distinction between architecture and معماری becomes legible here. The modern architect is often positioned as a producer of form, a solver of problems, an originator. The معمار, by contrast, operates within a prior order of meaning. The task is not invention but correspondence—measuring, gathering, and giving form in a way that allows intelligibility to appear. Space, in this register, is not neutral. It carries memory. It responds to care.

This difference is not semantic; it is ontological.

When architecture loses its relationship to the imaginal, it does not simply become secular. It becomes flat. Space collapses into surface, meaning into concept, and form into instrument. Buildings no longer orient; they perform. Images no longer disclose; they circulate. What remains is a landscape of stimulation without depth—spaces that demand attention without offering inhabitation.

This is not a moral judgment. It is a structural consequence.

Without the imaginal, architecture is forced to choose between two impoverished options: brute functionality or visual excess. In both cases, space becomes something to be managed, optimized, or consumed. What disappears is the possibility that space itself might teach, that form might invite reflection, that the built environment might participate in the cultivation of inwardness.

Yet the imaginal has never vanished entirely. It persists wherever space is treated as a threshold rather than an object, wherever light is allowed to arrive rather than be imposed, wherever proportion, rhythm, and material restraint make room for something other than themselves. It appears quietly—in the way a passage slows the body, in the way a courtyard gathers sound, in the way an opening frames the sky without claiming it.

Architecture, at its most lucid, does not seek to explain the world. It prepares one to encounter it.

Kader Attia, Holy Land. Installation, Canary Islands, 2006. A meditation on the promised land and those lost at sea.

This is the wager of imaginal architecture: that space can still serve as a site of correspondence between worlds; that form can carry meaning without fixing it; that the built environment can remind us—without instruction—that reality exceeds what is immediately given.

What this ultimately opens toward is not nostalgia, nor a return to historical forms, but a deeper question: what kind of world do our spaces presume, and what kind of human being do they quietly cultivate?

That question does not end with imagination.

It points beyond it.

If the imaginal is the world where meaning takes form, transcendence is the horizon that prevents meaning from closing in on itself.