Transcendence, in its deepest sense, does not announce itself as an idea to be grasped. It appears as a change in the way one exists.

To speak of transcendence meaningfully requires a fundamental shift in how knowledge, reality, and the human being are understood. Within the tradition of hikmat al-mutaʿāliyah—transcendent wisdom—transcendence is not conceived as a departure from the world, nor as an ecstatic rupture that bypasses reason. It is the culmination of a long process of becoming: a refinement of existence itself, through which the soul gradually aligns with the deeper structures of reality. Knowledge here is not an accumulation of representations, but a transformation of being.

Within this tradition, philosophy is not primarily a system of arguments, nor a catalogue of concepts. It is a discipline of transformation, ordered toward the refinement of the soul’s mode of being and its capacity to encounter reality. Mullā Sadrā, who stands at the center of this tradition, did not understand wisdom as something one possesses. Wisdom is something one becomes.

This orientation already marks a decisive departure from modern habits of thought. Knowledge is not neutral information about an external world, nor is it a subjective construction imposed upon inert matter. Knowledge is an existential event—a gradual intensification of being, in which the knower is altered by what is known. To know truly is to be reconfigured.

For architecture, this is not a marginal philosophical curiosity. Architecture, too, shapes modes of being. It conditions how bodies move, how attention gathers, how memory settles, and how meaning is encountered. If transcendence is real—not as abstraction, but as lived orientation—then architecture cannot remain ontologically indifferent. It must answer to the question of what kind of becoming it enables.

Existence Before Essence

At the heart of transcendent wisdom lies a deceptively simple claim: existence is primary.

Rather than treating existence as a secondary attribute added to fixed essences, this tradition understands existence (wujūd) as the most fundamental reality. Essences are not the building blocks of the world; they are the ways in which existence becomes determinate, intelligible, and perceptible. They are limits, contours, and garments—necessary, but not ultimate.

This shift has far-reaching consequences. The world is no longer composed of static substances awaiting classification. It is a living field of existence appearing in innumerable modes. Reality is not exhausted by what something is; it unfolds through how intensely it exists.

Such an ontology resists reduction. It does not collapse the world into matter, nor dissolve it into ideas. Instead, it opens a vertical dimension within being itself: existence comes in degrees, stronger and weaker intensities, more and less luminous modes. Unity and multiplicity are no longer opposed; they are reconciled through gradation.

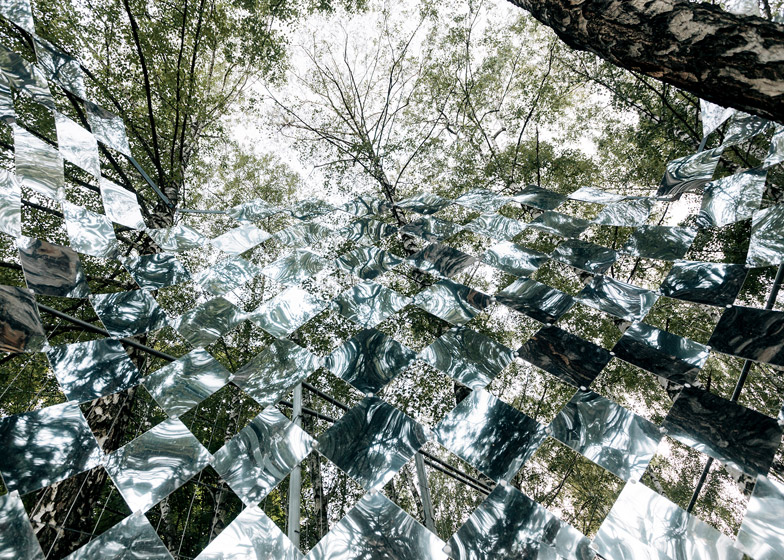

For architecture, this means that space is never merely physical. It participates in the modulation of existence. Light, proportion, enclosure, and threshold are not neutral variables; they shape how existence is felt, inhabited, and intensified. Architecture becomes a participant in the drama of being—not as creator, but as mediator.

A World Always in Motion

If existence is primary and graded, then the world cannot be static.

One of the most radical gestures of Mullā Sadrā’s philosophy is the affirmation of substantial motion: the claim that beings are not fixed substances undergoing accidental change, but are themselves processes of becoming. Change does not occur merely on the surface of things; it unfolds within their very reality.

The human soul, in this view, is not a stable subject accumulating experiences while remaining essentially unchanged. It is a traveler through states of being, renewed at every moment. Each encounter—sensory, imaginal, intellectual—contributes to what the soul becomes. Identity is not given once and for all; it is achieved through motion.

This insight transforms how we understand both ethics and space. Becoming is not arbitrary. Motion has direction. Some paths refine being; others disperse it. Wisdom lies in discerning the trajectories that lead toward greater coherence, clarity, and presence.

Architecture, when understood through this lens, ceases to be a static backdrop for life. It becomes a field of passage. Sequences, thresholds, pauses, and returns matter because they participate in shaping how one moves through the world—and through oneself. Architecture can accompany this becoming, but it can also flatten it.

Flattening does not mean the absence of movement. It means the loss of depth. When space is organized to privilege speed over pause, access over threshold, visibility over orientation, becoming is reduced to sequence rather than transformation. One moves through many moments without being altered by them. Experience accumulates, but nothing intensifies. Change occurs, yet no inner differentiation takes place. In such conditions, ascent is not rejected; it simply becomes unnecessary. What disappears is not motion, but the possibility that motion might lead somewhere.

Knowing as Transformation

To know something is not merely to hold a concept of it in the mind. In its most complete sense, knowing is a process in which the knower becomes adequate to what is known. The intellect is transformed until it coincides with the intelligible reality it seeks. Classical formulations speak of the unity of knower and known—not as mystical metaphor, but as ontological claim.

This means that truth is not grasped from the outside. It is entered. The more one knows, the more one is altered. Knowledge, in this sense, carries ethical weight. It demands preparation, discipline, and sincerity. It cannot be rushed or instrumentalized.

Such a view stands in sharp contrast to modern epistemologies that treat knowledge as detachable from the knower—as data that can be accumulated without consequence. Transcendent wisdom insists instead that every act of knowing reshapes the soul.

Architecture, too, participates in this economy. It does not merely communicate meanings; it educates perception. It trains the senses, attunes attention, and prepares the knower for encounter. The question is never only what a space signifies, but what kind of knowing it makes possible.

Knowing as Transformation

Transcendence is not opposed to imagination. It presupposes it.

Between pure intelligibility and material appearance lies the imaginal realm—a real order of being where meanings take form without becoming material. This realm is not psychological fantasy, nor symbolic decoration. It is an ontological domain with its own coherence, its own laws, and its own mode of perception.

In transcendent wisdom, the imaginal is indispensable. It mediates between intellect and sense, allowing truths that exceed abstraction to become encounterable. It is the realm of visions, dreams, symbolic forms, and subtle embodiment. Without it, transcendence would remain inaccessible; without transcendence, the imaginal would risk enclosure.

Architecture has always drawn from this intermediary world, whether explicitly or not. Sacred geometry, light modulation, narrative space, and rhythmic repetition are not aesthetic flourishes. They are imaginal strategies—ways of allowing meaning to appear without being exhausted.

Why Transcendence Feels Distant Today

If transcendence feels implausible or inaccessible in contemporary life, the reasons are not merely intellectual. They are structural.

Modernity has trained us to equate reality with what can be measured, optimized, and controlled. The intellect has been narrowed to calculation; imagination to fantasy; wisdom to information. The very faculties required for transcendence—patience, inwardness, disciplined attention—have been eroded by speed, fragmentation, and constant stimulation.

This is why speaking of transcendence today requires care. It cannot be asserted as doctrine, nor imposed as belief. It must be prepared for. Presence, imagination, and illumination are not alternatives to transcendence; they are its conditions.

Architecture, in this context, carries a quiet responsibility. It can either reinforce distraction and enclosure, or it can help recover the conditions under which transcendence remains thinkable. This does not require religious symbolism or historical imitation. It requires restraint, orientation, and fidelity to limit.

Toward Transcendent Architecture

Transcendent architecture is not a style, nor a revival, nor a claim to sanctity.

It is an orientation of making grounded in an ontological humility: the recognition that no form can contain what exceeds it, yet some forms can prepare us to encounter it. Such architecture understands its task not as expression, but as clearing—making room for attention, silence, and inward motion.

Its success is not measured by impact or visibility, but by the quality of presence it allows. It does not seek to explain transcendence. It knows when to withdraw.

In this sense, transcendent architecture stands at the far edge of form. It is faithful to existence as becoming, to knowledge as transformation, and to wisdom as lived passage. It accompanies the soul toward its source—not by enclosing the sacred, but by opening paths toward it.

A Bridge Forward

This entry has traced the ontological ground of transcendence: existence as graded, beings as in motion, knowledge as transformation, imagination as real mediation.

The entries that follow will move differently.

The next will turn toward practice and comparison—how diverse traditions, not only European ones, have preserved pathways of orientation, restraint, and ascent within fractured worlds.

The final entry will approach the limit itself—the point where even architecture must fall silent, and fidelity is measured by what remains unclaimed.

For now, it is enough to stand here—at the place where becoming becomes intelligible, and form remembers its source.